This Is For You

On the problem of perceived benevolence.

As a journalist I was trained to always ask people how to spell their names. “Even if it’s ‘Smith,’” the city editor would say, “always, always ask.”

And I was trained as a journalist to publish corrections. Even for small things. Even embarrassing things. Accountability demands that if you were an idiot and didn’t listen and didn’t ask, “How do you spell that?” you print a little notice that says it’s Smyth.

I didn’t do that but I was warned into imagining the feeling. This was an important part of the training because journalists think this is how you win trust. Demonstrate integrity. Follow the rules of your training, producing work that is accurate, fair, thorough, balanced, transparent, and has all the names spelled right.

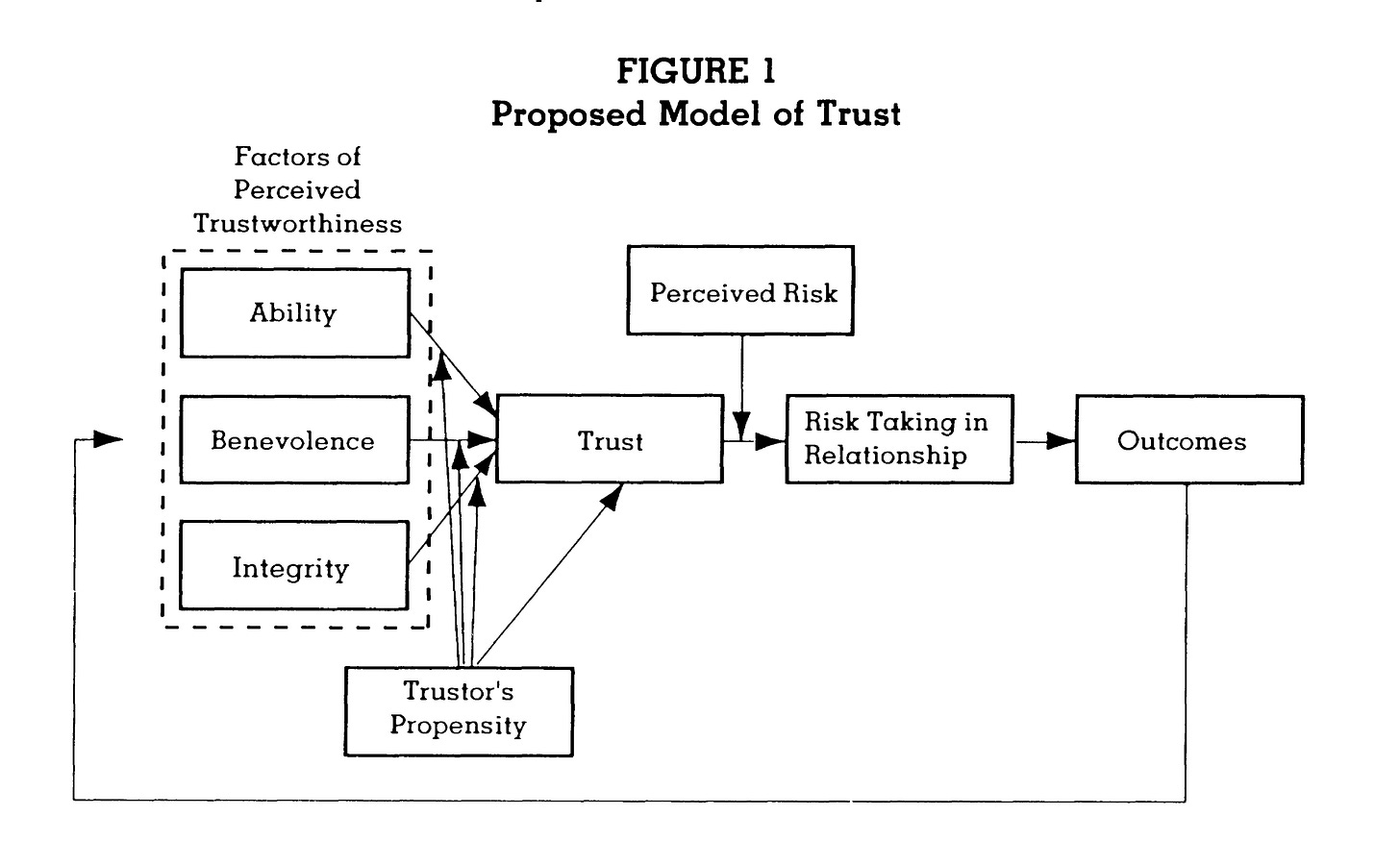

All of that’s good. I believe in all of that. But it misses another piece of trust: perceived benevolence.

Some really interesting research in media studies shows this is a key thing, an essential building block of trust.

If people are going to trust you, they have to think you have integrity. They have to think you’re good at your job. And they have to think you care about them and people like them, and that you like them, and want the best for them. If people are going to trust you, they have to believe you are for them.

I was not trained, as a journalist, to demonstrate love for readers.

The Case of GQ

The top editor at GQ magazine has made some major changes in the last decade, narrowing the scope of the magazine. GQ used to run longform journalism on basically everything. It was a magazine for men and anything interesting to men was fair game.

Now, Will Welch recently said on the interview podcast Talk Easy, it’s more like a magazine about pants. The focus is men’s fashion. The magazine has a niche. Everything they publish has to be in that niche.

Part of the story here, as Welch explains, is the story of the transformation of the media landscape. Fracture, narrow-casting, personalized algorithms, etc., etc., have challenged the massness of mass media. For most publications, it just doesn’t work anymore to try to be “general market.” If you’re for everyone, you’re for no one.

But this has also always been true. You have to find your people. You have to find your niche. You have to be for someone specifically. A magazine has to have a specific pitch. Like, hey, do you want to read about pants?

Daniell with Two Ls

The Atlantic misspelled my name once. Not “Silliman.” They got that right. They misspelled “Daniel.”

I couldn’t get anyone to correct it. I tried. I don’t know.

The Case of the Broken Bread

In my church we take communion every Sunday, passing the trays in the pews. Mostly, people don’t say anything when they pass. But a few weeks ago the person sitting next to me said, “Christ’s body, broken for you.”

Man, I love that phrase. I like the prepositional power it has, emphasizing the movement and purpose. The bread is moving to me. Jesus came to earth, to us, is called “Emmanuel,” with us, and his body was broken for us.

Hearing the words reminded me of the story I heard of a group of seminarians debating penal substitution. Is Christ’s death best understood in judicial terms? Should it be conceived as financial debt? There are also medical metaphors from church history and ideas like mimetic theory and Christus Victor.

A professor intervened and said don’t forget it’s for you.

Whatever the best theological explanation of the mechanics of salvation—how it works that Christ’s death works—a good account should start with the fact it works for you. It should include the prepositional power of the crucifixion.

Multiple Metaphors in One Direction

Augustine mostly used medical metaphors for the crucifixion in his preaching in Africa in the early 400s. He describes sin as sickness and God as a doctor, prescribing the cross as a cure. But he uses others too. I read one sermon recently where sin was a sea and Jesus, a fish. (Um. Sure?)

Augustine also hops around between metaphors and he notes, at least in one sermon, the potentially confusing multiplicity. But just look at descriptions of God in the Bible. Sometimes God’s a lion. Sometimes, an eagle. Sometimes, a mother hen. Even though, you know, those are not similar things.

Obviously this is partly because language is insufficient for God. Augustine says our language is such that “everything can be said about God, and nothing that is said is worthy of God.”

But there’s another reason, too.

As Augustine preached in Hippo in 407: “God becomes everything for you, because he is for you the fullness of the things that you love. … If you are hungry, he is bread for you. If you are thirsty, he is water for you. If you are in the dark, he is light for you, because he abides imperishable. And if you are naked, he is the garment of immortality for you.”

A familiar customer came into my grandfather's small town store to pay a deposit on an item. He had forgotten her last name and was embarrassed. To spur his memory and not seem untrustworthy, he said as he started to jot her information, "How do you spell your name?" Annoyed, she replied, "S M I T H."

I’ve been wondering about how to build trust with new potential “partners” in my own line of work, lately. I’ve received a few stingingly late and laconic replies that left me thinking, “This person just sees me as a salesperson.” It feels slimy. And I want it to be untrue.

“Blessed are the pure in heart,” Jesus said. Those words have stuck in my mind lately, as well. Gregory of Nyssa and Augustine alike saw “purity” as wholehearted pursuit of virtue; I wonder if one of its immediate implications might be “acting without concern for my own benefit.” Your article makes me think I need to fit love in there as a positive motive, to fill the negative space.

Recently, a friend who once attended seminary with me congratulated me on my new job “in sales.” I could make a lot of money, selling something “really important” if I continue down that track, he encouraged me. Popular ways of sharing the good news of Jesus sound a lot like “sales,” too. How would Jesus, purest in heart, go about the task of demonstrating his trustworthiness today? I’m reminded of his long walk near the end of Luke’s gospel, where he engaged earnestly with two crestfallen followers of the Way, until his breaking of the bread brought all the lights on. Maybe they, too, needed more than just a message but the (apparently) defeated, crucified Jesus to come near and rebuild trust.